I grew up aspiring to do things myself – isn’t that what men do?

Along with not feeling and certainly not showing my emotions, I worked at being self-reliant. To ask for help was showing weakness. The thought that another could impact my experience, or that I could unknowingly impact another, was not possible.

My first experience with Ron Kurtz, the developer of Hakomi Therapy, the leading somatic-psychotherapy, immediately proved my beliefs wrong. Instead, I saw how; others unconsciously felt unconscious responses to interactions of others. A subtle autonomic change in facial expression, shift in voice tone, or skin color change picked up by one person produced a response in another person – without conscious awareness. With training and practice, you could learn to use these micro-behaviors to support a man to deepen his connection to himself and others.

As you may have seen, as one man experiences an authentic feeling, others often have a similar response. One man shares how he feels trapped when his wife tells him she can’t feel him. The more he tries, the more she can’t feel him. He starts to cry as he says he loves her and feels like no matter what he does he can connect to his wife.

You look around the room and other men are also crying. The resonance of the man’s story and experience triggers other men to feel emotions they didn’t know they had.

Some explain this as mirror neurons — similar to those of the man sharing — firing off in others. Of late, some question this phenomenon. A more accepted explanation is that we co-regulate.

Stephan Porges’ Ph. D. research with the Vagus Nerve (the 10th cranial nerve) shows us that all mammals down-regulate the stress response by connecting to another. A baby stops crying when held. A scared patient relaxes when a loved one holds his hand. A man in a group expresses an old feeling when his group connects to his fear.

Our ROC (Relax, Open, and Connect) formula sets us up to fall in sync with one another.

As we connect — more often unconsciously — we increase our emotional and physiological resiliency and window of tolerance – along with neuroplasticity and tone.[i] When childhood trauma and stress occurred and was not physiologically completed often, we didn’t feel we were in an emotionally safe space where we could allow the physiology and emotions to run their natural course. Possibly the opposite occurred; others directed their fear towards you, a child who had no way to respond assertively. You need the love of your parents; consequently, you held back your natural response.

In our groups and couples workshops, the opposite occurs — we feel, and others accept those feelings as valid. As a result, we not only relax, but we also feel what was not felt in the past. With that, we are able to complete the physiological cycle and release held physical and emotional tension.

In the safety of others’ nervous systems feeling safe, our nervous system not only down-regulates in that moment, more importantly, our body also begins to learn how to down-regulate itself. So, for example, a child learns — or does not learn — how to calm himself by how well others trained him via co-regulations.

Begin to become more attuned to how you feel and express. Also, start noticing how that safety trains each one of you to bring it to others. Safety begets safety.

Dive deep into co-regulation by each person sharing how as a kid it wasn’t safe to feel. Share less from the analysis or story of it and more from experience. You may feel the emotions you could not fully feel about a past incident AS you tell it. Allow others to be the emotional safety you did not have in that past incident.

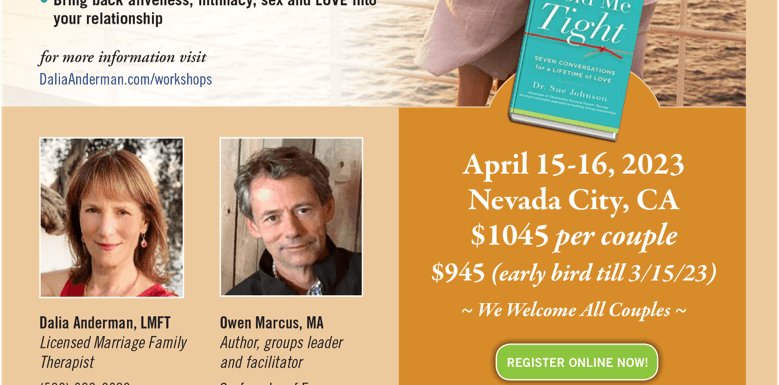

As a someone shares, feel their activation and ability to stay open to feeling your response. That is the key! By accepting your response, you are modeling and training another person that it is okay to feel and share his response. By stretching yourself to feel, you are serving the entire others. This is the essence of the power what we teach in our Hold Me Tight weekend couples’ workshops.

Hold Me Tight is a registered mark of Sue Johnson, Ph.D.

[i] A term coined by Dan Siegel, MD, which is adapted into a guide to trauma treatment by Pat Ogden, Ph. D. Refers to the range of specific emotions, affective intensity, or physiological arousal a person can tolerate before becoming dysregulated and hyperaroused or hypoaroused. Expansion of window of tolerance is a common goal across many complex trauma interventions. https://www.complextrauma.org/glossary/complex-trauma